Stomach-Churning Rating: 1/10 unless I change my mind and add some unsavoury images (which I did not).

A most un-creative title for a most un-creative post topic. I’ve been short on new ideas for the blog for a long time, and short on energy for them. Furthermore, I’ve been more busy trying to get specimens out of my freezers and reduced to bones, rather than getting new specimens and doing new anatomical work on them, which might otherwise be good fodder for blog posts. I’d love to do a new “Better Know a Muscle” post, but that is hard work. Yet a good old standby post, a summary of stuff I’ve coauthored lately that grabs my immediate fancy, is fine. So here is that summary; most recent papers first.

1. Hutchinson, J.R., Pringle, E.V. 2024. Footfall patterns and stride parameters of Common hippopotamus (Hippopotamus amphibius) on land. PeerJ 12:e17675. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.17675

This one got a ton of media attention, much more than I expected. And in a week that was far from slow news (UK election, ever-crazier USA politics, so on). I think the media liked a fun distraction that reminds us how the natural world still has its wonders and how scientists are still doing goofy stuff. I’ve long wanted to do a study of hippo locomotion, as part of my opus on how giant land animals move, so I recruited vet undergrad Emily Pringle to go film hippos at Flamingo Land Resort in North Yorkshire (who’ve been immensely supportive of our research). She set up GoPro cameras and filmed what she could over 2 days. It wasn’t much. The two hippos just walked slowly in and out of their night-time barn now and then. But we had a cunning plan. Emily also searched the internet (mostly Youtube) for more videos showing a wider range of speeds, and I added some more after her project. The upshot is, hippos only use trotting gaits (diagonal limbs moving in near-unison) from slow to fast speeds (walking trots to running trots), and at fast speeds they go airborne for substantial periods of time. That’s cool for two reasons: (1) it’s odd for a (large) mammal to just trot and not use the usual walk-trot-canter-gallop series of gaits; and (2) it wasn’t known (or even asked, much) in scientific literature if hippos did go airborne or not.

I cringe a little at how simple this work is, but there’s still great value in observation and a “data paper” as I regarded this one. Still, I like it and it fills a lacuna in our understanding, and takes my research a step further toward what I’d like to know (e.g., what constraints influence locomotion at giant sizes, and how those evolved in particular lineages). I’ve never written a paper so quickly. It took maybe a week from start to submission. It’s not rocket science, but it’s useful. It has gotten me more motivated to expand this hippo research into some novel directions. A little more about the paper on Twitter.

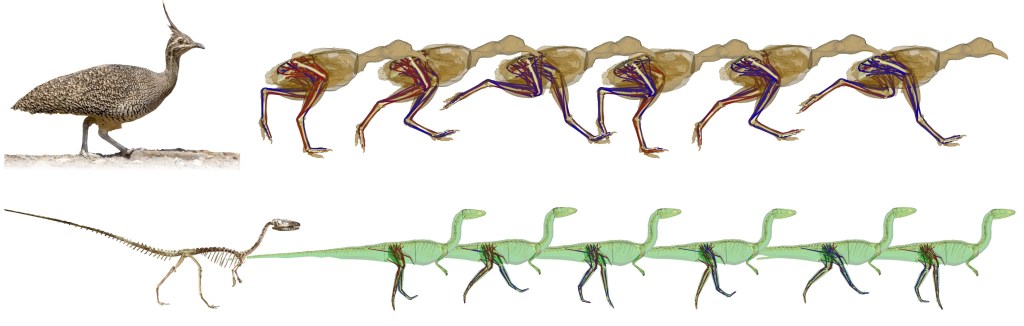

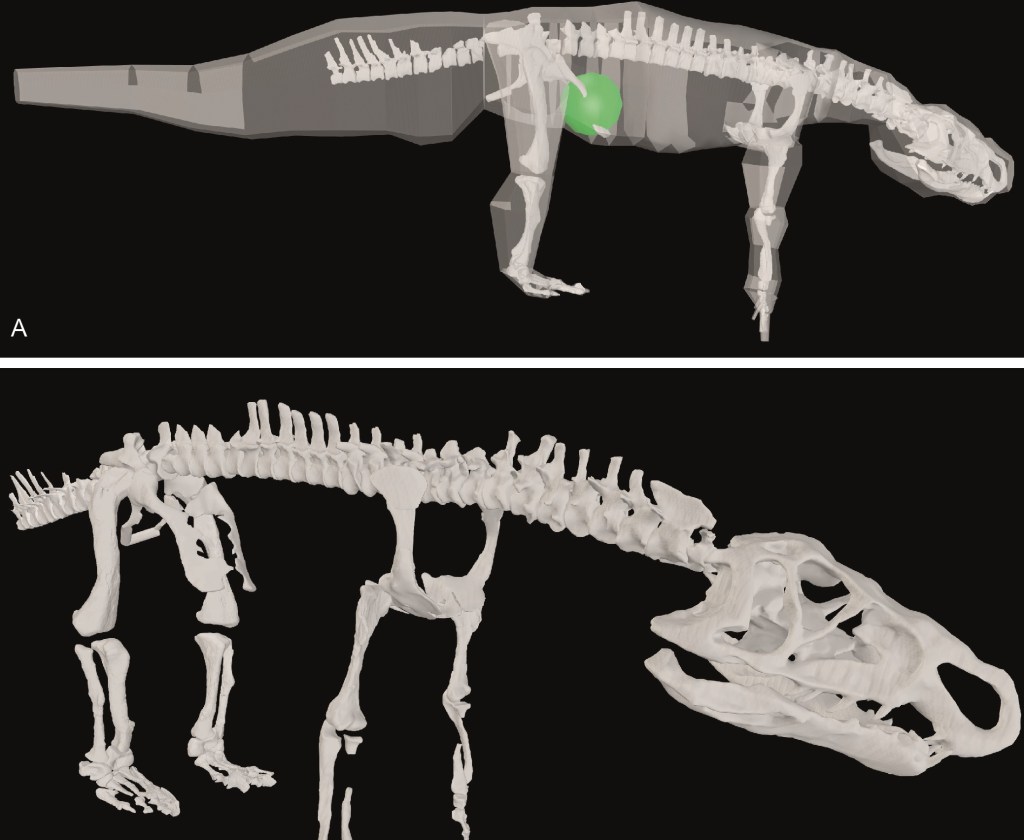

2. von Baczko, M.B., Zariwala, J., Ballentine, S.E., Desojo, J.B., Hutchinson, J.R. 2024. Biomechanical modelling of musculoskeletal function related to the terrestrial locomotion of Riojasuchus tenuisceps (Archosauria: Ornithosuchidae). Anatomical Record 25528. https://doi.org/10.1002/ar.25528

A new DAWNDINOS grant paper; #41 published so far from that project (since 2017), with many many more to come. I enjoyed writing this one, quite a bit. The subject is a member of a small clade of very strange crocodile-line archosaurs (ornithosuchids) from the Triassic period. They have a long history (>100 years) of study and ideas about them have roamed widely, such as what they were more closely related to (theropod dinosaurs? No. Early dinosaurs and pterosaurs? No.). And how they moved: bipedally and/or quadrupedally? Sprawling to erect limb posture? Plantigrade (flat-footed) or digitigrade (tip-toed)? We did our standard approach of scanning the skeletal remains of Riojasuchus tenuisceps, making a 3D musculoskeletal model, and then using that to address lingering questions like those I’ve mentioned. We found the evidence for/against bipedalism to be wonderfully ambiguous, which might sound strange to say, but I like that Riojasuchus tenuisceps remains a conundrum. It is weird. But we were convinced that it used quite erect and plantigrade postures. There’s a lot more to the paper such as consideration of the evolution of hindlimb musculature but that gets really technical. We’ll be doing more with this model, involving deeper biomechanical analysis, in the near future. Here, again, an RVC undergrad, Sarah Ballentine, got involved in the early stages of modelling. A little more about the paper on Twitter.

3. Etienne, C., Houssaye, A., Fagan, M., Hutchinson, J.R. 2024. Estimation of the forces exerted on the limb long bones of a White Rhinoceros (Ceratotherium simum) using musculoskeletal modelling and simulation. Journal of Anatomy, published online. https://doi.org/10.1111/joa.14041

Much as I’ve long wanted to study hippos as one of the “big four” clades of giant land mammals, I’ve wanted to do so with rhinos; and this is my fifth such study. Here, we (led by French PhD student Cyril) use the same kind of 3D musculoskeletal modelling process as paper #2 above, but including real data from dissections of muscles from a white rhino, and usage of those data in a simple static simulation to estimate how the muscles might be activated to support a quiet standing pose, and what the corresponding muscle and joint forces might be. Surely because it supports more weight, the forelimb had greater muscle activations and forces; especially from some lower limb muscles such as the ulnaris lateralis (an elbow extensor) and digital flexors; and the humerus experienced the greatest forces, reflecting its robust morphology. This is a step toward other kinds of modelling such as finite element analysis of bone stresses. Cyril put in a huge effort to build a nice model and conduct careful analyses with complex input and output data, and he cleverly designed some nice figures of those data.

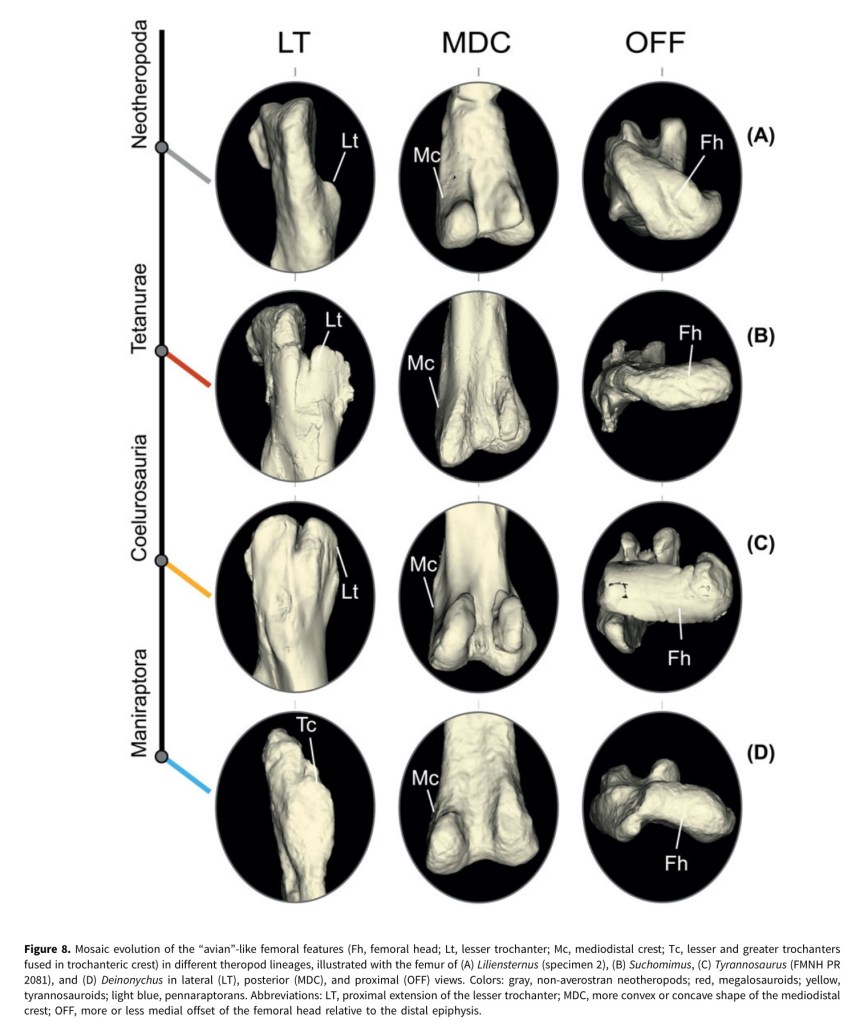

4. Pintore, R., Hutchinson, J.R., Bishop, P.J., Tsai, H.P., Houssaye, A. 2024. The evolution of femoral morphology in giant non-avian theropod dinosaurs. Paleobiology, 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1017/pab.2024.6

A dinosaur paper, imagine that! This one came from 1st author Romain’s PhD and some data we collected during the DAWNDINOS grant; and quite a bit of data that he wrangled during the COVID pandemic lockdowns. The data are 3D scans of 68 specimens from 41 species of Mesozoic theropods, then subjected to 3D geometric morphometrics shape analysis, to see what features related to giant body size or to other things (e.g., more “birdlike” traits). Each time theropods reached giant (>1000 kg) body sizes, their femora (thigh bones) attained many similar aspects of shape, but also more of those “birdlike” traits kept accumulating (and convergently evolving) along the theropod family tree, and even in some giant forms, and especially in “miniaturised” theropods. I like how this paper ties together two of my big research themes, how giant size influences form and function, and how archosaurian/dinosaurian locomotion evolved; and in the context of rich 3D anatomy. And Romain did some stellar work assembling a huge dataset with very rigorous analyses — and gorgeous figures in the paper!

5. Kurz, M.J., Hutchinson, J.R. 2023. Visual feedback influences the consistency of the locomotor pattern in Asian elephants (Elephas maximus). Biology Letters 20230260. https://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2023.0260

Hippos, then rhinos, and now elephants! How grand. This paper feels like it was ages ago, and the data collection was — we did the experiments involved back in 2006! Co-author Max Kurz and I wondered, how much would the slow walking patterns of elephants be disrupted if we removed their capacity to see? This question ties into how elephants maintain “stability” (a fraught term in science). Stability is clearly of great importance to giant land animals following “the bigger you are, the harder you fall” principle. Compared to walking with vision, blindfolded elephants were able to keep the duration of each stride close to the average (in one way remaining “stable”) but the noisiness (“consistency”) of their stride decayed across multiple strides, so they tended to take slower or faster strides as they walked across their paddock. This decay would increase the chances of a stumble or fall as blind elephants moved over longer periods. Thus it shows how vision removes that risk, aiding these giant animals in maintaining “stability”. It’s a neat little experiment. We had the paper all written back in 2010 but held back, then in 2023 I decided to go for it and submit what we had; and I am glad we did that. A little more about the paper on Twitter.

6. Lacerda, M.B.S., Bittencourt, J.S., Hutchinson, J.R. 2023. Macroevolutionary patterns in the pelvis, stylopodium and zeugopodium of megalosauroid theropod dinosaurs and their importance for locomotor function. Royal Society Open Science 10230481230481 http://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.230481

and

7. Lacerda, M.B.S., Bittencourt, J.S., Hutchinson, J.R. 2023. Reconstruction of the pelvic girdle and hindlimb musculature of the early tetanurans Piatnitzkysauridae (Theropoda, Megalosauroidea). Journal of Anatomy 244:557-593. https://doi.org/10.1111/joa.13983

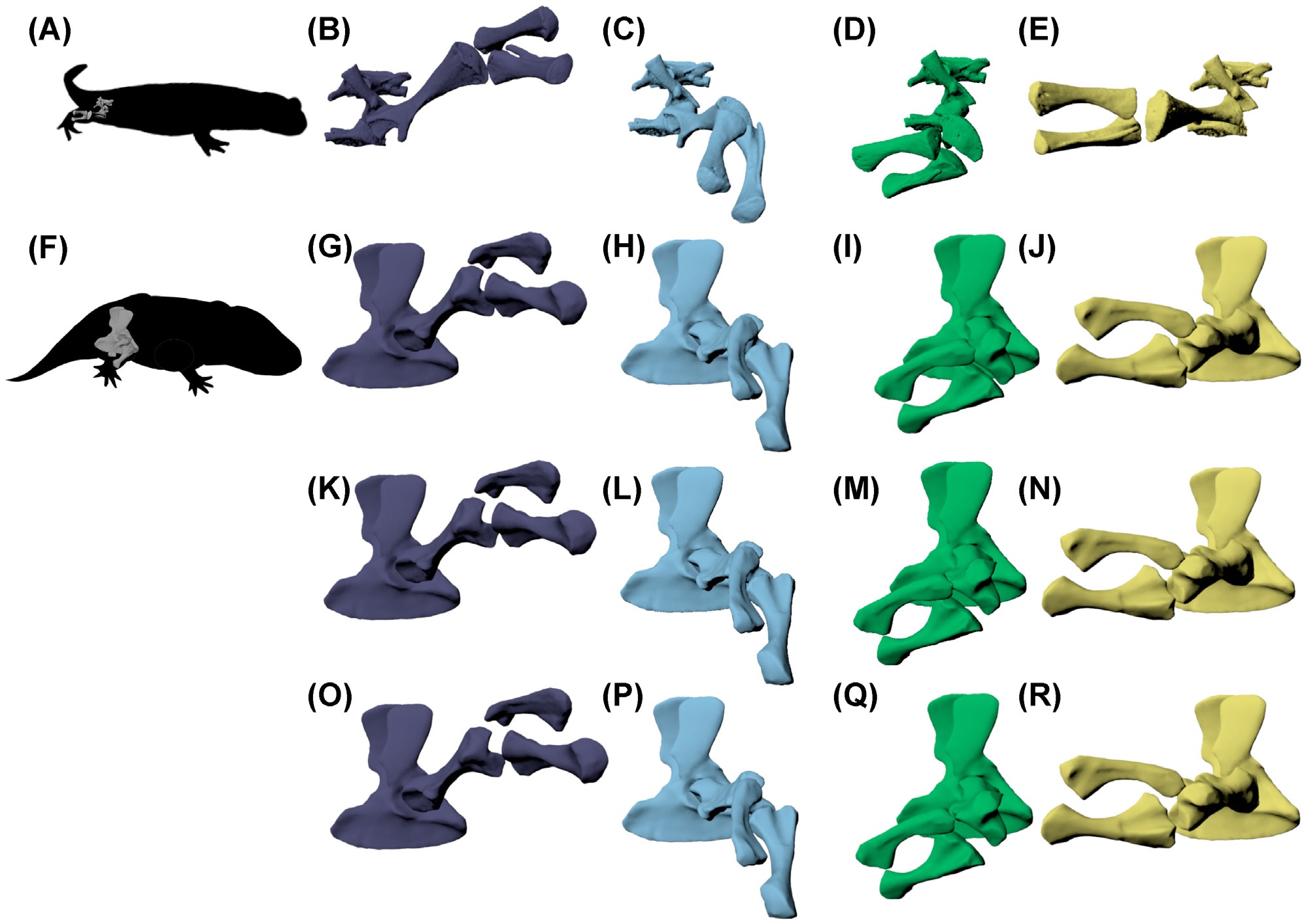

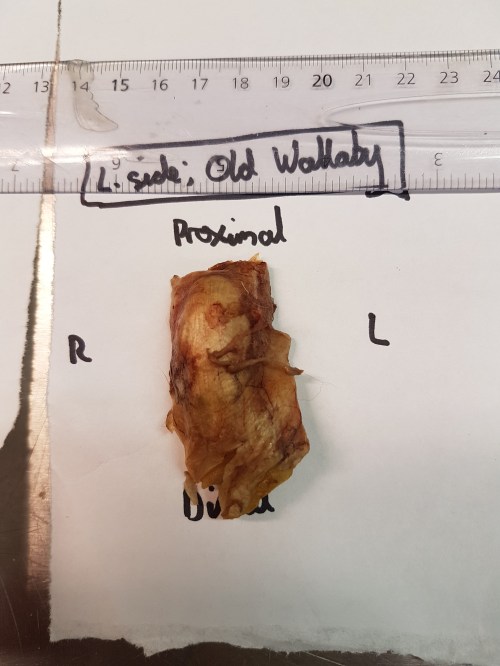

Brazilian PhD student Mauro Lacerda joined my lab for a sustained period back in 2022, to collaborate on learning how to reconstruct the hindlimb musculature of theropod dinosaurs and use such data in 3D biomechanical modelling. It has been a really fun and productive collaboration, with at least two more papers yet to come. Mauro had been focussing on the “intermediate” theropods (not ‘early’ ones like coelophysoids and ceratosaurs; not ‘late’ ones like carnosaurs and coelurosaurs, but in a hazy in-between phylogenetic position), called Megalosauroidea. As the name indicates, this clade includes the oldest named dinosaur, Megalosaurus (happy 200th birthday!). Many members are Jurassic forms from around the world, often of medium-large size and rather robust build; but also the celebrity dinosaurs, Spinosauridae, are embedded within Megalosauroidea. We set out to first characterise how key skeletal traits of the hindlimbs of these animals evolved, building a nice pictorial and phylogenetic “atlas” of sundry bumps and squiggles on the bones, and mapping how the distribution of those traits compares across groups of early theropods in a “morphospace”. It’s detailed work that should be a helpful reference for all of those working on this interesting clade of theropods and their relatives.

The second study built on the first, by applying methods and evidence I’ve formalised for reconstructing the (hind)limb muscles of theropods and other archosaurs/tetrapods. We estimated where the muscles of three megalosauroids (Condorraptor, Marshosaurus, and Piatnitzkysaurus in order of improved fossil preservation) originated from and inserted onto, where possible. Some bones or regions of bone were unpreserved, limiting what we could estimate, but this is an aspect of the study that I like, as it is a comparative exercise in how much taphonomy influences what we can infer about soft tissues and their evolution across extinct lineages. And it makes possible the usual kinds of 3D biomechanical analyses that my group does — stay tuned for that.

So there you have it. Hippos, early archosaurs, rhinos, earlier and later theropod dinosaurs, and elephants. Lots of locomotor anatomy, biomechanics and evolution. This pretty much sums up my research career and current foci. The variety is part of what makes my job so fun, but the central issues keep it chugging along to push the boundaries of knowledge forwards in my little corner of science. Moreover, it’s a lot of collaboration, around the world and with researchers at different career stages and in varied disciplines from biology to palaeontology to engineering. I love that variety, too. I’m particularly pleased in this set of papers that I’ve included some undergrads, which I’ve been trying to get better at, but which takes some careful planning of studies and persistence (and time!) to get the papers out the door after the students move on.