I’ve been doing some osteological studies of the patella (bone in the major tendon in front of the knee; termed a sesamoid) that have included frequent visits to the Natural History Museum’s avian skeleton collection at Tring. It’s a cute little town, northeast of London, in the green county of Hertfordshire where I live and work. The museum at NHM-Tring is a great old school multi-storey display packed with skeletons and stuffed animals in dark wood cabinets, with many critters hanging from wrought iron railings or other suspensions above (see above). I blogged about the Unfeathered Bird exhibit (and book) that just finished up its tour there yesterday. And I’ll be blogging later, as I keep promising, about the cool things I’ve learned during the past year of my studies of the form, function, development and evolution of the patella.

As an aside, I heartily recommend doing research at the NHM-Tring. It’s away from the bustle (and arduous Tube trip) of the South Kensington NHM, and the curatorial staff are immensely helpful… and there is something else that makes the trip even more enjoyable, but you must read more below to find out about it.

Stomach-Churning Rating: 2/10; 150-year-old dry bones. But an advance warning to (1) diabetics and (2) pun-haters, for reasons that will become evident.

Dr Heather Paxton and Dr Jeffery Rankin, postdoc researchers working on our collaborative BBSRC chicken biomechanics grant (see thechickenofthefuture.com), use the Structure & Motion Lab whiteboard to explain their science to an attentive Darwin.

Today I have a short pictorial exhibit of something wonderful I ran into while patellavating in the NHM collections. As often happens while doing museum research, I had a serendipitous encounter with a bit of history that blew my mind a little, and had me geeking out. These things happen because museum collections are stuffed with specimens that, to the right eyes or the right mindset, pack a profound historical whallop. As a scientist who is pretty keen on chickens (Gallus gallus), there are probably no museum specimens of chickens that would get me more excited about than the chickens Darwin studied in his investigations of artificial selection. In fact, most museum specimens of domestic chickens would not be that interesting to me, especially after seeing these ones.

Darwin wielded the analogy between artificial selection and his conceptual mechanism of natural selection in the first ~4 chapters of On the Origin of Species to clobber the reader with facts and try to leave them with no doubt that, over millennia, nature could craft organisms in vastly more complex and profound ways than human breeders could mould them over centuries. While people most often speak of Darwin’s pigeons when referring to Darwin and avians or artificial selection and variation, his chickens appear in The Origin and other writings quite often, too (most prominently, The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication in 1868– more about that here). For example, from my 1st edition facsimile of The Origin from Harvard University Press, pp. 215-216:

“Natural instincts are lost under domestication… It is not that chickens have lost all fear, but fear only of dogs and cats, for if the hen gives the danger-chuckle, they will run… and conceal themselves in the surrounding grass or thickets; and this is evidently done for the instinctive purpose of allowing, as we see in wild ground-birds, their mother to fly away. But this instinct retained by our chickens has become almost useless under domestication, for the mother-hen has almost lost by disuse the power of flight.”

Well told, Mr D!

I am also reminded of how chickens and Darwin have had darker relationships, such as this sad story. Or how evolution via Darwinian mechanisms crosses paths with pop culture in fowl ways, such as how tastes-like-chicken evolved, or how some say that chickens, over great periods of time, have been naturally selected in such a way that they are now heritably predisposed to cross roads, or that the amniote egg preceded the evolution of the genus Gallus by some 325+ million years. I see I am drifting and drifting further away from the topic at hand, so let me segue back to Darwin’s chickens. We’ll take this corridor there:

Inside the avian osteology collection at Tring. Sterile at it might outwardly seem, places like this are fertile breeding grounds for scientific discovery. And a sterile-looking collection means well cared-for specimens that will persevere for future discoveries.

So anyway, when museum curator Jo Cooper said to me something like “I have some of Darwin’s chickens out over on the other counter, do you want to have a look or shall I put them away?” my answer was quick and emphatic. YES! But only after lunch. I was hungry, and nothing stops me from sating that hunger especially when the sun is out and there are some fine pubs within walking distance! I settled on the King’s Arms freehouse, and had a delicious cheeseburger followed by a spectacularly good apple-treacle-cake with ice cream, expediently ingested while out on their sunny patio. Yum! I cannot wait to have that cake again. What a cake! Darwin’s bushy eyebrows would have been mightily elevated by the highly evolved flavour, which would have soothed his savage stomach ailments. He would have been like:

“Damn, Emma! Holy s___ this is great apple-cake; here, try some! There is grandeur in this tasty cake, with its several flavours, having been originally cooked into a few baking trays or into one; and that, whilst this pub has gone on serving fine food according to the fixed hygiene laws of Tring, from so simple a beginning endless foods most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, devoured.” And Emma, cake then firmly in hand, would have said something like, “My dear Charles, I shall try this enticing dessert, and I am glad to see you so enthused about something other than barnacles. Write a letter to Huxley or Lyell about that cake later. You need to focus on concocting an ending to that big species book of yours, not cakes. It’s been 20 bloody years, dude; cake can wait. End the book on a high note.” And so it must have happened.

Working at a museum collection is like having an extra home/office for a day or more. You get familiar with the environment while working there, and start to settle in and enjoy the local environs while taking work breaks. Or I do, anyway. So this post is also partly about how cake and other provisions are an important part, or even a perk, of life as a visiting museum researcher. Put in some good solid work, then it’s cake time, but where are the cakes? You explore, and you discover them– opening the door of an unfamiliar shop or pub near a museum can be like opening a museum cabinet to discover the goodness inside. Just don’t get them mixed up. Museum specimens: for research; subjects for science. Cakes: for eating; fuel for scientists. Got it?

But I digest digress. This post is not about my lunch. Not so much, anyway, although I did enjoy the cake quite a bit. Back to the chickens. Here, try some!

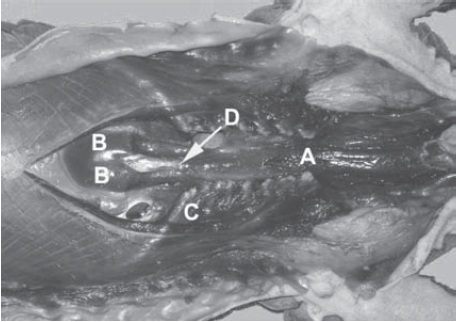

Above: Views of Darwin’s chickens laid out at the NHM-Tring. (all photos in this post can be clucked to emchicken them)

The chickens, much like the pub lunch, did not disappoint in the least. Here I had before me Darwin’s own personal specimens, which I envisioned him dissecting and defleshing himself, studying them in deep introspection, then handing them over to the museum for curation once his lengthy researches were complete (all the ones I studied dated back to around 1863-1868, so they were curated shortly after The Origin was published (1859)). Perhaps the museum gave him some fine sponge-cake in return. There was at least one male and female adult of each of numerous breeds, many of them still bearing the dried flesh of centuries past. This was great for me, as the patella often gets removed and clucked chucked in the bin with its tendon when museum specimens of birds are prepared (much as elephant “sixth toe” sesamoids are). All of the specimens had their honking huge patellae on display, so that’s what a lot of my photos feature. I do so lament that I did not take a photo of the cake. Did I tell you about that cake? Oh… Check out these examples of Darwin’s chickens:

African rooster (wild variety? Darwin’s label was not clear) in right side view, with the patella indicated by a red arrow. That patella is still attached to the tibiotarsus by the patellar tendon (often misnamed the patellar “ligament”, but it is just a continuation of the proximal tendon).

Darwin’s handwritten label and the well-endowed patella of the Spanish Cock. What? Oh, you. Stop it. That has nothing to do with cake, and only cake-related humour is allowed in this post.

Some other fascinating features exhibited by Darwin’s chickens, which he doubtless mulled over while nibbling on fine cakes, included the following:

The hindlimb of a Polish Silver Laced breed, nicely showing the ossified tendons (red arrow) along the tarsometatarsus. Why these tendons turn into bone is one of the great unsolved mysteries of bone biology/mechanics and avian evolution.

Check out the famed feather crest of the Silver (Laced) Polish here; it gets so extreme in males that they have a hard time seeing, and can get beaten up by other cockerels when kept in mixed breed flocks.

Here on this blog, and of course on the companion blog “Towards the Chicken of the Future,” domestic chickens and wild junglefowl have often come up, most recently with the Dorking Chicken (another of Darwin’s own specimens that I studied) in the “Mystery Museum Specimen” poetry round of late. Dorkings are HUGE chickens; easily twice the weight of even a broiler chicken, up to 4-5kg. The Dorking-characteristic polydactyly featured in that post is also observed at a relatively high incidence in Silkie and Sultan breeds, I’ve learned. Like this one! (I was so patella-focused, or cake-somnolescent, that I missed it while studying at the museum and only noticed it now while browsing through my photos, bereft of cake)

Nice leg of a Sultan hen. There is an extra toe here as in the Dorking chicken; a duplicate hallux (first toe). This is not, as it might at first seem, a pathological condition as in modern “twisted toe”-suffering domestic chickens.

Malays are another giant breed like the Dorking, but with longer and more muscular legs and longer necks, looking much more like a classic, badass wild junglefowl than a fancy, pampered chicken. But here, undressed to the bare bones, it just looks like a skinny chicken leg, albeit perhaps a bit svelte compared to the Dorking or Sultan.

Hindlimb of a Malay breed of chicken, which Wikipedia nicely tells the story of its misnomer (it may originate from Pakistan, not Malaysia!). Can you find the nice patella? Check out Darwin’s lovely label, too.

You may have come across wild-eyed news stories 5 years ago about “OMG Darwin was sooooooo wrong about chickens!”, referring to his writings on the origin of domestic chickens from Red junglefowl. As Greg Laden adeptly wrote, Darwin (say it with me) didn’t really get it very wrong after all. He did quite well, in fact. Some media outlets did get it more wrong, probably inspired by this press release. Oh well; the science they were reporting about definitely was interesting- modern chickens seem to have some of their yellow skin pigmentation-related genes from Grey junglefowl, although they are still largely descendants of Red junglefowl.

Here, have a JUMBLE-fowl, or rather a junglefowl cockerel, with another Darwin label:

Darwin’s example of a wild-type chicken; a Red junglefowl. As he suspected, these Asian birds were the ancestors of domestic chickens, but today evidence indicates that domestication may have occurred multiple times in Asia and with different wild varieties of junglefowl bred/mixed in different regions.

Some breeds aren’t so funky inside, of course, but just have cool feather patterns on the outside, like the “pencilling” (dark streaks on white feathers) evident in pencil breeds; also called triple-laced. Like this fine chap below once would have had, before Darwin tore off his feathers and reduced him to a research-friendly naked skeleton:

A Golden Pencil(led) Hamburg breed of chicken (cockerel), whose skeleton features the leg and a fine articulated patella.

Also known as the Holland Fowl, several European countries including the UK claim the Hamsburg as an original breed from their respective realm, and no surprise they do- it’s a lovely spangled chicken. Then, later in the 1800’s the Americans got involved in breeding them, too, and it’s all a big mess. They should get together, have some delectable cakes, and just sort it out.

We thus close with another leg of another chicken. Darwin was a bit naughty here, or else terminology of breeds has changed a lot since the 1850’s (very possible), as he just labelled this as a “Game” cockerel. Now, Gamefowl is a big category of breeds. I’m guessing this one was either (1) a Cornish/Indian Game variety or (2) an Old or Modern English Game Fowl. Maybe a person who knows their chicken breeding far better than me (that’s not hard!) will opine differently. The latter varieties were popular in Darwin’s time — the (Muffed) Old English version was mated with other breeds (Malay?) to produce the Modern English form as cockfighting “sports” became banned in 1849 and breeder attentions shifted to the polar opposite of producing showy, fancy birds instead. And thus the bufante, feathered-hair-adorned 1980s pop-rock group was created, to sing about mating or moulting or melting with people or something terribly disgusting and probably having nothing at all to do with chickens, cake, or cockfighting, or other more seemly pursuits.

So, we have come to the end of my photos of Darwin’s chicken leg bones and such. If you’ve learned something here about chicken breeds, patellae, cake, or Darwin, that’s simply frabjous. Enough of those poncey pigeons, already! I’m crying fo… no, I won’t use that pun. Nevermind. Not even remotely cake-related. Let’s give Darwin’s chickens their just desserts, is the point– and a much better pun, too. Darwin’s chickens are an important part of Darwiniana, and an interesting evolutionary study in and of themselves. I’ve certainly become impressed during my researching for this blog post by the diverse, fascinating biology of chicken breeds. My copy of the “Complete Encyclopedia of Chickens” will be getting some more thorough reading shortly.

Today, however, I am off to return to the NHM-Tring and peruse their other, non-chickeny Galliformes and Anseriformes, with a detour to the mythical hoatzin. But… but… there may be a cake detour involved, too. I shall report back in due course. Off I go!

No, hopefully not that cake.